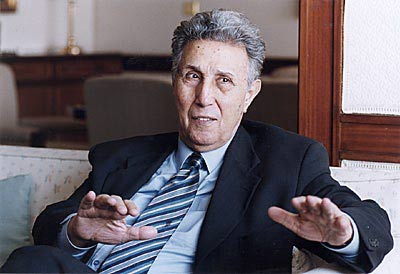

original name David Gruen

born Oct. 16, 1886, Płońsk, Pol., Russian Empire [now in Poland]

died Dec. 1, 1973, Tel Aviv–Yafo, Israel

Zionist statesman and political leader, the first prime minister (1948–53, 1955–63) and defense minister (1948–53; 1955–63) of Israel. It was Ben-Gurion who, on May 14, 1948, at Tel Aviv, delivered Israel's declaration of independence. His charismatic personality won him the adoration of the masses, and, after his retirement from the government and, later, from the Knesset (the Israeli house of representatives), he was revered as the “Father of the Nation.”

Ben-Gurion, born David Gruen, was the son of Victor Gruen, one of the leaders in Płońsk of the “Lovers of Zion,” a movement that was disseminating among the oppressed Jews of eastern Europe the idea of the return to their original homeland of Israel. Zionism fascinated the young David Gruen, and he became convinced that the first step for the Jews who wanted to revive Israel as a nation was to immigrate to Palestine and settle there as farmers. In 1906 the 20-year-old Gruen arrived in Palestine and for several years worked as a farmer in the Jewish agricultural settlements in the coastal plain and in Galilee, the northern region of Palestine. There he adopted the ancient Hebrew name Ben-Gurion. Suffering the hardships of the early pioneers, including malaria and hunger, he never lost sight of his goal. It was owing to his efforts that the 1907 convention of his Zionist socialist party, Poale Zion (“Workers of Zion”), included the following declaration in its platform: “The party aspires to the political independence of the Jewish people in this land.”

With the outbreak of World War I, the Turkish governors of Palestine, their suspicions aroused by his Zionist activity, arrested Ben-Gurion and expelled him from the Ottoman Empire. During the height of the war, he traveled to New York, where he met and eventually married the Russian-born Pauline Munweis. In the last stages of World War I, the British supplanted Turkish rule in the Middle East; and with this change the Jewish settlers and their friends and supporters abroad began to realize that Zionism could rely for future assistance on Britain as well as on the wealthy and influential segments of American Jewry. Following the British government's publication on Nov. 2, 1917, of the Balfour Declaration, which promised the Jews a “national home” in Palestine, Ben-Gurion enlisted in the British army's Jewish Legion and sailed back to the Middle East to join the war for the liberation of Palestine from Ottoman rule.

The British had already defeated the Turks when the Jewish Legion reached the battlefield, and, when Britain received the mandate over Palestine, the work of realizing the “Jewish national home” had begun. For Ben-Gurion, the “national home” was a step toward political independence. To implement it, he called for accelerated Jewish immigration to Palestine in the effort to create a Jewish nucleus that would serve as the foundation for the establishment of a Jewish state. That nucleus was the Histadrut—the confederation of Jewish workers in Palestine founded in 1920 by Ben-Gurion (who was elected its first secretary-general) and his colleagues. The Histadrut rapidly became a central force in social, economic, and even security affairs, attaining the position of a “state within a state.” Ten years later, in 1930, a number of labour factions united and founded Mapai, the Israeli Workers Party, with Ben-Gurion at its head. In 1935 he was elected chairman of the Zionist Executive, the highest directing body of world Zionism, and head of the Jewish Agency, the movement's executive branch.

As the Jewish settlement strengthened and deepened its roots in Palestine, anxiety mounted among the Palestinian Arabs, resulting in violent clashes between the two communities. In 1939 Britain changed its Middle East policy, abandoning its sympathetic stand toward the Jews and adopting a sympathetic attitude toward the Arabs, leading to severe restrictions on Jewish immigration and settlement in Palestine. Ben-Gurion reacted by calling upon the Jewish community to rise against England, thus heralding the decade of “fighting Zionism.” On May 12, 1942, he assembled an emergency conference of American Zionists in New York City; the convention decided upon the establishment of a Jewish commonwealth in Palestine after the war. At the end of World War II, Ben-Gurion again led the Jewish community in its successful struggle against the British mandate; and in May 1948, in accordance with a decision of the United Nations General Assembly, with the support of the United States and the Soviet Union, the State of Israel was established.

David Ben-Gurion became prime minister and minister of defense. Through internal political struggles that incensed both the right and the left, he succeeded in breaking up the underground armies that had fought the British and in fusing them into a national army, which became a model and symbol of the maturing Israeli nation and an effective force against the invading Arab armies from Syria, Jordan, Iraq, and Egypt. Although the fighting ended with an Israeli victory, the Arab leaders refused to enter into formal peace negotiations with the Jewish state.

Ben-Gurion viewed the newborn state as the direct continuation of Jewish history that, in his opinion, had been interrupted 2,000 years earlier when the Roman legions had crushed the Hebrew freedom fighters and banished the Jews from Palestine. He saw the Jews' period of exile as a prolonged interlude in the history of Israel and declared that they had now regained their rightful home. In order to strengthen and develop the young nation, Ben-Gurion presented the people of Israel with a series of challenges: the absorption of mass immigration from all over the world; the assimilation of newcomers of diverse communities and backgrounds; the creation of a unified public education system; the settlement of the desert lands. In his foreign policy, he adopted an independent and pragmatic course. He used to say: “What matters is not what the Gentiles will say, but what the Jews will do.” His defense policy was firm, and he answered violations of the cease-fire agreements by neighbouring Arab states with military reprisals.

His stronghanded policy inspired little sympathy for him from the governments of the United States and Britain. They preferred more moderate leaders such as Chaim Weizmann, first president of Israel, and Moshe Sharett, who was elected prime minister for a brief term (1953–55) when Ben-Gurion temporarily retired from office. Striving to gain a foothold in the Middle East, the U.S.S.R. alienated Israel by providing the Arabs with vast quantities of arms. At that time, Ben-Gurion found an ally in France. During the war in Algeria, France encountered the opposition of the united Arab front, led by Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser, and consequently drew closer to Israel, supplying it with considerable amounts of military equipment; when Nasser nationalized the Suez Canal in July 1956, French initiative brought Israel to join the Franco-British military campaign against Egypt. On Oct. 29, 1956, following a secret visit to France and a meeting with French and British leaders, Ben-Gurion ordered the army to take over the Sinai Peninsula, while France and Britain were making an abortive attempt to seize the canal. Israel subsequently withdrew from Sinai after having been assured freedom of navigation in the Strait of Tiran and de facto peace along the Egyptian-Israeli border, which was to be supervised by a special United Nations force.

Following the Sinai campaign, Israel entered a period of diplomatic and economic prosperity. Ben-Gurion was head of government until 1963. During his last years of office, he initiated several plans (which proved fruitless) for secret talks with Arab leaders with a view to establishing peace in the Middle East.

In June 1963 Ben-Gurion unexpectedly resigned from the government for unnamed “personal reasons.” His move apparently resulted in part from the bitter internal controversy between his supporters and his rivals in the party, who rose against him for the first time because of the political implications of the 1954 “Lavon Affair,” involving Israeli-inspired sabotage of U.S. and British property in Egypt. The affair led Ben-Gurion in 1965 to leave Mapai with a number of his supporters and to found a small opposition party, Rafi, at the head of which he fought, with little success, against his successor, Levi Eshkol.

In 1970 Ben-Gurion retired from the Knesset and from all political activity, devoting himself to the writing of his memoirs in Sde-Boqer, a kibbutz in the Negev. He published a number of books, mostly collections of speeches and essays. Through most of his life he had also engaged in researches into the history of the Jewish community in Palestine and in the study of the Bible.

original name David Gruen

original name David Gruen