Introduction

(see Researcher's Note)Early life and career

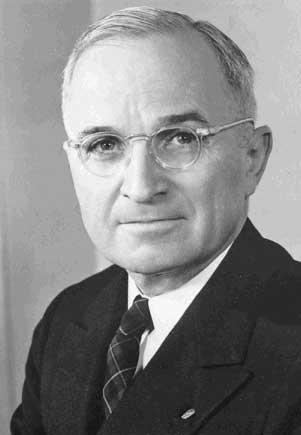

Truman was the eldest of three children of John A. and Martha E. Truman; his father was a mule trader and farmer. After graduating from high school in 1901 in Independence, Missouri, he went to work as a bank clerk in Kansas City. In 1906 he moved to the family farm near Grandview, and he took over the farm management after his father's death in 1914. When the United States entered World War I in 1917, Truman—nearly 33 years old and with two tours in the National Guard (1905–11) behind him—immediately volunteered. He was sent overseas a year later and served in France as the captain of Battery D, a field artillery unit that saw action at St. Mihiel and the Meuse-Argonne. The men under his command came to be devoted to him, admiring him for his bravery and evenhanded leadership.

Returning to the United States in 1919, Truman married Elizabeth Wallace (Bess Truman), whom he had known since childhood. With army friend Edward Jacobson he opened a haberdashery, but the business failed in the severe recession of the early 1920s. Another army friend introduced him to Thomas Pendergast, Democratic boss of Kansas City. With the backing of the Pendergast machine, Truman launched his political career in 1922, running successfully for county judge. He lost his bid for reelection in 1924, but he was elected presiding judge of the county court in 1926, again with Pendergast's support. He served two four-year terms, during which he acquired a reputation for honesty (unusual among Pendergast politicians) and for skillful management.

In 1934 Truman's political career seemed at an end because of the two-term tradition attached to his job and the reluctance of the Pendergast machine to advance him to higher office. When several people rejected the machine's offer to run in the Democratic primary for a seat in the U.S. Senate, however, Pendergast extended the offer to Truman, who quickly accepted. He won the primary with a 40,000-vote plurality, assuring his election in solidly Democratic Missouri. In January 1935 Truman was sworn in as Missouri's junior senator by Vice President John Nance Garner.

He began his Senate career under the cloud of being a puppet of the corrupt Pendergast, but Truman's friendliness, personal integrity, and attention to the duties of his office soon won over his colleagues. He was responsible for two major pieces of legislation: the Civil Aeronautics Act of 1938, establishing government regulation of the aviation industry, and the Wheeler-Truman Transportation Act of 1940, providing government oversight of railroad reorganization. Following a tough Democratic primary victory in 1940, he won a second term in the Senate, and it was during this term that he gained national recognition for leading an investigation into fraud and waste in the U.S. military. While taking care not to jeopardize the massive effort being launched to prepare the nation for war, the Truman Committee (officially the Special Committee Investigating National Defense) exposed graft and deficiencies in production. The committee made it a practice to issue draft reports of its findings to corporations, unions, and government agencies under investigation, allowing for the correction of abuses before formal action was initiated.

Respected by his Senate colleagues and admired by the public at large, Truman was selected to run as Franklin Delano Roosevelt's vice president on the 1944 Democratic ticket, replacing Henry A. Wallace. The Roosevelt-Truman ticket garnered 53 percent of the vote to 46 percent for their Republican rivals, and Truman took the oath of office as vice president on January 20, 1945. His term lasted just 82 days, however, during which time he met with the president only twice. Roosevelt, who apparently did not realize how ill he was, made little effort to inform Truman about the administration's programs and plans, nor did he prepare Truman for dealing with the heavy responsibilities that were about to devolve upon him.

Succession to the presidency

Roosevelt died suddenly of a cerebral hemorrhage on April 12, 1945, leaving Truman and the public in shock. He told reporters the day after taking the oath of office that he felt as if “the moon, the stars, and all the planets had fallen” on him and asked them to pray for him. He was hardly, however, as scholars have noted, a political naif. Although he had no foreign policy experience, he was a capable administrator of large bureaucracies and a skilled politician who knew how to use the press to his purposes.

Truman was sworn in as president on the same day as Roosevelt's death, which was just weeks away from Truman's 61st birthday. He began his presidency with great energy, making final arrangements for the San Francisco meeting to draft a charter for the United Nations, helping to arrange Germany's unconditional surrender on May 8, and traveling to Potsdam in July for a meeting with Allied leaders to discuss the fate of postwar Germany. While in Potsdam Truman received word of the successful test of an atomic bomb at Los Alamos, New Mexico, and it was from Potsdam that Truman sent an ultimatum to Japan to surrender or face “utter devastation.” When Japan did not surrender and his advisers estimated that up to 500,000 Americans might be killed in an invasion of Japan, Truman authorized the dropping of atomic bombs on the cities of Hiroshima (August 6) and Nagasaki (August 9), killing more than 100,000 men, women, and children. This remains perhaps the most controversial decision ever taken by a U.S. president, one which scholars continue to debate today. (See Sidebar: The decision to use the atomic bomb. See also primary source document: Announcement of the Dropping of an Atomic Bomb on Hiroshima.) Japan surrendered August 14, the Pacific war ending officially on September 2, 1945.

Winning a second term

As the presidential election of 1948 approached, the odds against Truman's winning the presidency seemed enormous. The Republicans had triumphed in the congressional elections of 1946, running against Truman as the symbol of the New Deal. That electoral triumph seemed to indicate that the American people were weary of reform and of the Democratic Party. Worsening Truman's chances for reelection was the defection of liberal Democrats, breaking with the president over his hard-line opposition to the Soviet Union; many of these liberals supported the candidacy of Henry A. Wallace, who was running as the Progressive Party candidate for president. At the Democratic National Convention, Southern delegates bolted as well, angry at the president for his strong civil rights initiatives; these Southern Democrats supported Strom Thurmond, the States' Rights (“Dixiecrat”) presidential candidate. But Truman surprised everyone. He launched a cross-country whistle-stop campaign, blasting the “do-nothing, good-for-nothing Republican Congress.” As he hammered away at Republican support for the antilabour Taft-Hartley Act (passed over Truman's veto) and other conservative policies, crowds responded with “Give 'em hell, Harry!” The excitement generated by Truman's vigorous campaigning contrasted sharply with the lacklustre speeches of Republican candidate Thomas E. Dewey, and Truman won by a comfortable margin, 49 percent to 45 percent; Wallace and Thurmond had little impact on the outcome. (See primary source document: Inaugural Address.)

Energized by his surprising victory, Truman presented his program for domestic reform in 1949. The Fair Deal included proposals for expanded public housing, increased aid to education, a higher minimum wage, federal protection for civil rights, and national health insurance. Despite Democratic majorities in the House and Senate, most Fair Deal proposals either failed to gain legislative majorities or passed in much weakened form. Truman succeeded, however, in laying the groundwork for the domestic agenda for decades to come.

Outbreak of the Korean War

In June 1950 military forces of communist North Korea suddenly plunged southward across the 38th parallel boundary in an attempt to seize noncommunist South Korea. Outraged, Truman reportedly responded, “By God, I'm going to let them [North Korea] have it!” Truman did not ask Congress for a declaration of war, and he was later criticized for this decision. Instead, he sent to South Korea, with UN sanction, U.S. forces under General Douglas MacArthur to repel the invasion. Ill-prepared for combat, the Americans were pushed back to the southern tip of the Korean peninsula before MacArthur's brilliant Inchon offensive drove the communists north of the 38th parallel. South Korea was liberated, but MacArthur wanted a victory over the communists, not merely restoration of the status quo. U.S. forces drove northward, nearly to the Yalu River boundary with Manchuria. Hundreds of thousands of Chinese troops then poured into North Korea, pushing the fighting once again down to the 38th parallel. When MacArthur insisted on extending the war to China and using nuclear weapons to defeat the communists, Truman removed him from command—a courageous assertion of civilian control over the military. The administration was devoted to its policy of containment. The war, however, dragged on inconclusively past the end of Truman's presidency, eventually claiming the lives of more than 33,000 Americans and leaving a residual bitterness at home.

The inability of the United States to achieve a clear-cut victory in Korea following Soviet conquests in eastern Europe and the triumph of communism in China led many Americans to conclude that the United States was losing the Cold War. Accusations began to fly that the president and some of his top advisers were “soft on communism,” thereby explaining why the United States—without question the world's greatest power in 1945—had been unable to halt the communist advance. As the nation's second “Red Scare” (the fear that communists had infiltrated key positions in government and society) took hold in the late 1940s and early '50s, Truman's popularity began to plummet. In March 1952 he announced he was not going to run for reelection. By the time he left the White House in January 1953, his approval rating was just 31 percent; it had peaked at 87 percent in July 1945.

Over the next two decades, however, Truman's standing among American presidents rose. He began to be appreciated as a president who had, in Truman's own words, “done his damnedest.” The ultimate common man thrust into leadership at a critical time in the nation's history, Truman had risen to the challenge and acquitted himself far better than nearly everyone had expected. Later presidents, regardless of political party, looked back on him fondly, admiring his willingness to take responsibility for the country (as a sign on his desk read, “The Buck Stops Here!”) and trying to emulate his appeal to the average voter. His Fair Deal social programs, such as those delineating civil rights for African Americans, had been defeated during his presidency but were enacted in the 1960s and retained by Democratic and Republican administrations alike. Truman did, however, issue an executive order (9981) that desegregated the military, and he was noted for appointing African Americans to high-level positions. His reputation suffered slightly in the 1980s, when scholars highlighted the fact that in private conversation and personal correspondence, Truman told off-colour jokes and referred to minorities and ethnic groups in terms considered highly offensive today.

No comments:

Post a Comment